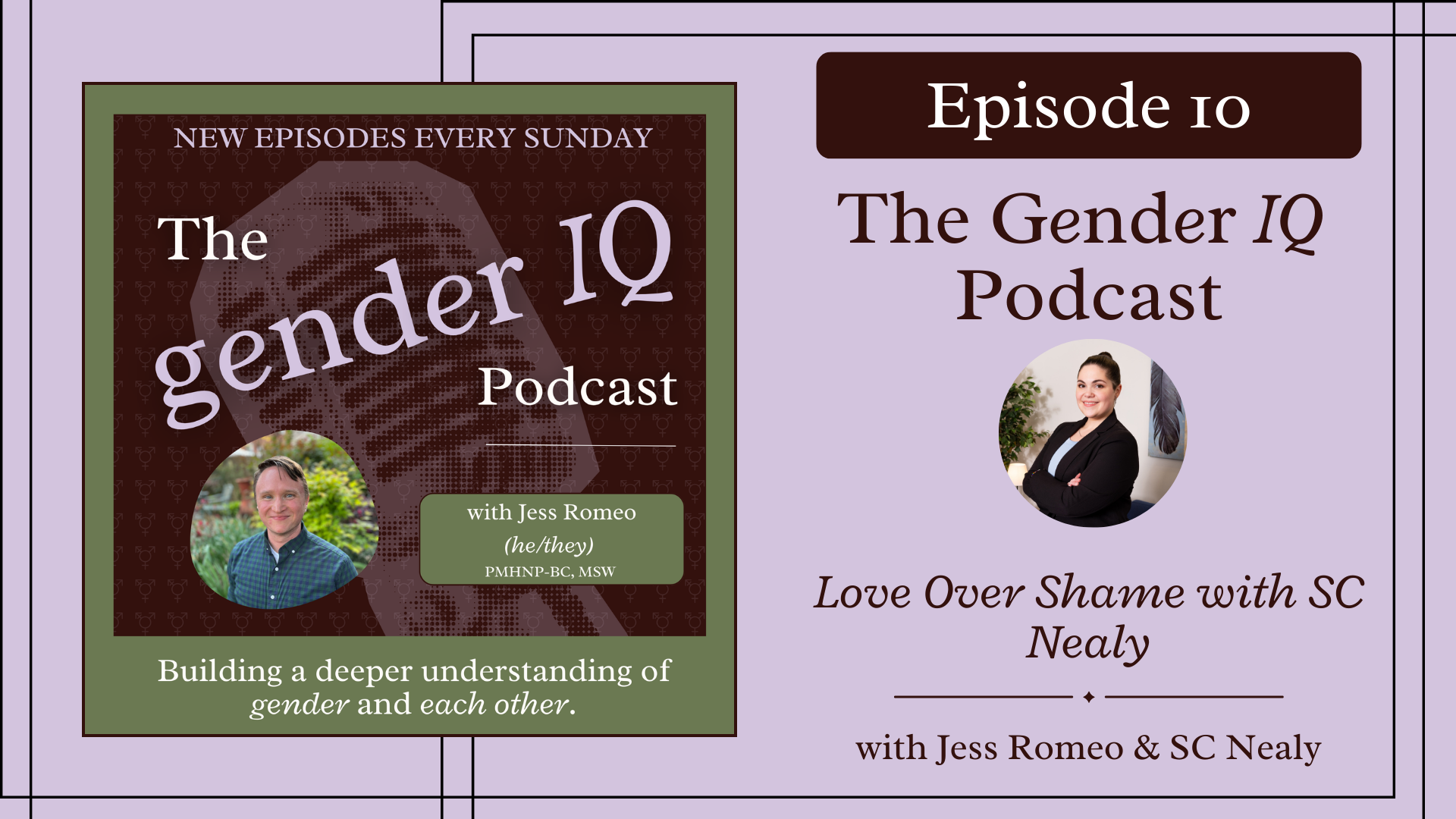

Episode 10: Love Over Shame

Religious Trauma, Recovery, and Queer-Celebratory Care with SC Nealy

Healing from religious trauma means reclaiming your story - on your own terms.

Episode Overview:

In this episode, Jess and SC Nealy explore what it takes to move from religious trauma to radical self-acceptance. SC shares their journey of navigating queer identity in the context of faith and how their experiences shape their therapeutic practice today. It’s a conversation about community, healing, and finding the freedom to live authentically.

About the Guest

With over 15 years in mental health, SC Nealy, LPC (they/them) wants their clients to feel heard, understood, and valued in the therapeutic space and in their lives. It is important to SC that clients learn how to love all parts of themselves, including the parts that they might think are unloveable. Personally, SC identifies as non-binary, gender fluid, and queer/lesbian and they specialize in their work with the LGBT+ population, religious trauma, complex post traumatic stress disorder, neurodivergence, female identifying couples counseling, premarital counseling, and more.

Liberation can sometimes mean rewriting the rules.

In this episode, SC Nealy shares how queer identity and spirituality intersect in their practice as a therapist. We explore what it takes to heal from religious trauma, build supportive community spaces, and reclaim identity from the scripts that never served us.

Together, we discuss:

✨ How religious trauma can uniquely impact queer and trans identities

✨ Rebuilding self-trust after being told your identity is a problem

✨ Finding your own spiritual path while honoring your truth

✨ The power of queer community in healing from shame

✨ Why affirming care means centering autonomy and choice

Transcript

Jess Romeo: Welcome to the Gender IQ Podcast. today I'm joined by SC Nealy - therapist, author, parent, and a powerhouse advocate for queer mental health in the DC Metro area. With over 15 years in the field and a focus on religious trauma and queer celebratory care, SC brings both depth and vulnerability to this conversation. We talk about what it means to create a queer celebratory practice, how religious trauma shows up in relationships and why leaving behind what's expected can sometimes be the most liberating path. There's a lot of insight here, a lot of heart.

And if you've ever wondered how someone can go from romance novelist to owner of a group psychotherapy practice, this is the podcast for you. Let's get into it.

SC Nealy: So I think it was always like very clear to me that I wasn't how I publicly identified, but I just spent a very, very long time trying to push that away. And I think the more comfortable I became with who I am, the more you could see that in my art. I didn't come out fully until I was 28, at least publicly. So it was a long time.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, that is a really long time. Like so many of us share that story

Jess Romeo: I'm so curious about you and how you got to be where you are. So can you tell us our story, your story and start from the beginning? I want to know everything that you're comfortable sharing.

SC Nealy: Okay, so I have been in mental health now for 15 years, maybe 16 or 17 at this point. And at first I was really spending a lot of time working in inpatient and residential. I did a lot of work in severe mental with individuals who were in more - either assisted living or group home situations, a lot of schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum-related illnesses. And then I also transitioned into eating disorder clinics and inpatient for quite some time and really enjoyed that as well. I think any time you work inpatient, residential, community-based, there's a timeline before you burn out. It's very intense work, very underpaid, a lot of hours.

And it's still like, to be fair, one of the most beneficial experiences I've ever had towards becoming really good at being a therapist. I think everyone should do it. But there is like a timeline. Like you can't do that forever without just being exhausted. And so eventually, you know, I had received my first master's in forensic psychology and I was working in prison settings, again, similar to that kind of residential. Very burnout can be really quick to happen there.

And I was finding that a lot of the work I was doing under that degree was less clinical and a little bit more administrative or something related to that. And I was finding that I was really lacking and really wanted to be more involved in the clinical side of things. I was also finding that I would come up to a lot of colleagues as - I was called too optimistic often. That came up a lot.

And I think that that's totally fair for people who are working in those settings that have had a lot of experience in that setting, that there is probably some cynicism and jadedness that comes with working in that setting for a long time, which is completely fair, but it's a path I did not want for myself to ever feel that way. Like that's not natural to who I am as a human being or my personality.

And so I really just decided to go back and get my second master's in clinical mental health counseling so that I could specifically be more in the clinical role and practicing I did my practicum and internship in different closed settings. like an employee assistance program, I did that for a little bit. Very interesting, but not really for me.

I worked in a detox program and substance abuse for women. Again, very interesting, but not really for me long term. And then after that, I started to get into group practices and working one-on-one with clients and really found that I loved that a lot more. I struggled, however, with finding a group practice that felt like a fit for me. I was going through my own sexual orientation, identity exploration, and all of that at that time.

And I was finding that whatever practice I was in, I was usually the only person who either was experiencing that or had an identity that was different from Cishet. And so sometimes I was beneficial because it was like any referral that came in that wasn't Cishet would go straight to me. And I got to work with that population more and I enjoyed that. But there was also like a loneliness to that at the same time and a feeling of othering that definitely came up with in my colleagues.

And when you're in a setting of all like cishet people, there's also some masking that you just have to naturally do or at least feel that you have to do. And so it just - while I really enjoyed a lot of aspects of the different places I worked and I learned a lot from different supervisors and other colleagues, there still was just not like a fit feeling.

And so I decided to go out on my own once I was fully licensed and had finished residency and all of that stuff. And I practiced solo for a while, which was great. But the big complaint that I had was just, again, the loneliness factor. I'm naturally an extrovert. I love community. I love people. I think that's one of the reasons why I do this job is working with people. certainly clients come in, and you're not lonely in that way. But it's a very different relationship and a lot more - there is still like masking and you have to put on a certain role and you have to up for other people. You don't necessarily get to explore or be your own self all the time. And so that led me to starting my own group practice.

I had a few things that were like really important to me when starting my own practice is like one, making it a space for queer and trans identifying therapists where we could all just feel like ourselves and not feel the need to mask in any way or hide anything but just show up as our authentic selves. And then two, to really focus on the burnout, the clinician burnout piece of making the practice that was really sustainable for one, therapists to get paid what they need to get paid and to feel comfortable, but also not to work an insane amount of hours. And I found that the collaborative piece is the way that I have found that has worked the best of everyone really feeling like a part of a team.

So our team, we have breakfast together every Thursday morning. We do events together. We all enjoy each other as friends. And then we also have a lot of professional collaboration where I might work with a couple and then someone else here works with one of the individuals in that couple or things like that. So there's a lot of, you know, teamwork or if someone's working with an adolescent, I'm working with the parents and then we do the family therapy together. And I find that that is really helpful for just feeling like you belong more in a place and you're accepted more in a place and personally feeling like that myself as well. So that has been kind of the big goal of this practice and we're just now celebrating our first year. So it's been still new and still learning and growing and hopefully continuing to grow but it's been really exciting and wonderful.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. And I'm really, and I said this in previous conversations, I've been really impressed with how much you have done with your practice in just a year. Like looking at, looking at, you know, the awards, some of the recognition and just name recognition around the DMV area. It's been like, "okay, I'm like taking notes." Folks who are - who are thinking about starting a group practice or expanding from solo to group. Like, I hope you're taking notes cause SC has done things really wisely, just taking a lot of great steps. Yeah. Yeah. I feel that for sure. Well, I'm really curious to know. I didn't get this in the timeline as you were talking about it, but like, which came first, therapist or romance novelist?

SC Nealy: Technically romance novelist, I guess. This was after my forensic psych masters that I started it, but before I was working clinically. I was just kind of at a crossroads in my life of didn't fully know what I wanted to do. I'd gone the forensic psych route, and it just wasn't what I wanted. And so I was kind of like, I don't know what I want to do.

And I wasn't ready at that time to like take on doing another master's in anything else. That just felt like - I'd just gotten out of school for eight years. Why would I go back? So I just wasn't emotionally ready to go back to school at that point. And I'd always enjoyed writing. I'd written poetry and short stories since high school and onwards. And I had thankfully came out with my first book, right? Just as e-books became a thing. Like the first year like Kindle was born and existed. And it was just a huge birthing moment for the ebook industry. And I just happened to luckily get in at that right time. The timing was good. And so, you know my books did really well, thankfully. And back then I was still like really trying to force myself to be cis and straight. And so a lot of my novels were as well. And the arc of like, if you look at the 30 romance novels that I've written, you can see my gender and sexual orientation change with each book.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, that's interesting. I didn't know there were so many. I think I saw referenced them on the Bonyard site, but I knew there were more. Yeah. So that - did it show up in the - this is what I'm endlessly curious about as an artist myself. And I think most of us entrepreneurs are also artists in some ways. Like, art tends to have this way of expressing our truest selves before we're ready to give it words and before we have words for it. So I kind of love this idea that the romance novels came to you before the realization of queerness. But I don't know if I'm totally making that up.

SC Nealy: Yeah. Yeah. It came before the realization of queerness. It came before I was open to accepting that part of myself, right? Like the first time I was told that I was a lesbian, I was six years old and it was my pastor screaming it at my dad that she's going to be a lesbian. And I was like, god, what is that? That sounds terrible. So I had always known.

Jess Romeo: At 6? That's young.

SC Nealy: Yeah. Yeah. I was a big tomboy.

When I grew up in a cult, I wasn't allowed to wear pants or cut my hair. So like, I was very clearly stood out from what was like, supposed to be how I was supposed to identify at that time. And then I had to come out again in high school, like asked a girl to prom and got, you know, raked over the coals by my family for that. And so went back to the closet. I tried to come out in college again in undergrad and instead just ended up in a four year secret relationship with somebody else who like neither one of us were gay, but we were just best friends who "we're a little bit more than best friends, we're just best friends," that kind of thing. So I think it was always like very clear to me that I wasn't how I publicly identified, but I just spent a very, very long time trying to push that away. And I think the more comfortable I became with who I am, the more you could see that in my art. I didn't come out fully until I was 28, at least publicly. So it was a long time.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, that is a really long time. Like so many of us share that story and even though I didn't, I mean, I come from a similar-ish place, right? Like being from the deep south, I wouldn't say that I grew up in a cult myself, but it was in the air, right? You breathe it even if it's not happening exactly in your home.

And so I just feel so much hope when I look at queer kids today of thinking, wow, okay, I came out the first time as a lesbian at 16. I was the first gay person most people in my high school or community knew, but then it took me 16 more years to realize, no, this whole gender thing is that's also a thing. Transitioning is right for me. And yeah, yeah. Yeah.

I vividly remember - I think I was a teenager and I felt like an alien in a lot of different ways. Like I was just kind of like nerdy theater kid in a jock's body. It was weird in many ways, but I listened, like I was listening to something on NPR and I really loved Katie Ling. Cause of course I did.

And she was talking about what it was like in Canada in a small town because the interviewer, it might have been Terry Gross or somebody like that, but the interviewer was like, wow, you grew up in a really small town. And to just clock this time-wise, it's probably like 2005 or so. It's like, wow, was that really hard? Like being gay in a small town, like, was it really tough? And she was just like, no, like I just, I didn't even know that there was really a word for it. I just had girlfriends. Like just, just how it went as if it was the most natural thing in the world.

And I remember thinking at like 14 or 15, like, god, what must that be like for it to just be a way that you can be without this whole to do about coming out? And are you going to be able to still go to college? Are you going to be able to stay at home? Are you going to have to go to one of those Christian counselors? Like, and now it feels so easy to say, of course, but yeah.

Well, with your - because we started talking about this because of romance novels. So at some point, was it like one book, like cis straight with one book and then queer in the next book? Or how did that end up going for you?

SC Nealy: I would have to look back at the timeline to be a little more familiar - after 30 books kind of blends together a little bit. I think that I had always had queer side characters.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, that would make sense. Yeah, I was going to say, did the queer side characters start increasing?

SC Nealy: Yeah, they started increasing. And I think that that was always culturally and socially more acceptable, right? The Will and Grace, the need - all of that. And so like that was always more okay and I felt more comfortable putting that in. It did take me a lot more time to switch to main characters who identified as queer. And I think I started that with like from a bisexual standpoint and then kind of moving more into, you know, some sort of monosexuality, identity, or things like that.

I always stuck with more sapphic and female identifying or non-binary identifying characters and storylines. The problem with that is there's just not a huge market for it. And there's a huge pushback from publishers. It's incredibly hard to get a publisher to pick up a lesbian romance. We've recently had some success in the last few years with Casey McQuinstin and people like that doing ones here and there, but if you look at like gay male romance versus lesbian and sapphic romances, like it's just - it's such a minor piece of the entire demographic and it's really frustrating. I really wish that there was a lot more sapphic and lesbian representation in writing in general, but specifically in romance for sure. It's still really lacking.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. Yeah, I'm assuming audience shifted a lot. Did your representation have to shift a lot? Were your publishers pushing back as things changed? Yeah.

SC Nealy: Yeah. It's really easy for me to call up a publisher right now and get a Cishet romance published. But I have yet to be able to get a traditional publisher to pick up a lesbian romance. You - usually I end up self publishing those. I have had them out on pitch for years and everyone just pushes back of like, there's just not enough of an audience for that. It doesn't have enough of a mass market or like airport feel to it. Right?

Jess Romeo: Well, and one thing that I was really excited about and seeing on your website is I had never seen or heard of the concept of sort of an asexual romance novel.

SC Nealy: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, so I had my first one. This is actually a big back and forth with the publisher. They first pitched it to me as they wanted me to write a Cishet virgin romance story where the guy takes the woman's virginity and that's the whole story. And I was like, absolutely not. It is 2024, or maybe it was 2023. Yeah, I was like, "I'm absolutely not doing that." And so I immediately like X'd out the whole thing and I was like, "I will write a virginity story that is asexual and a totally different reason for their virginity." And so they were okay with it. Thankfully, they didn't give me a huge pushback, which is big for mass market because mass market is like all those ones that are in like grocery stores and stuff like that.

I specifically wanted to write - it's more classified as aromantic. And so there's no sex in the book or any interest in that. And I couldn't technically use the word asexual or aromantic in the actual writing itself. I had to refer to it and reference it in order to have it pass through. But yeah, that was the concept of, "yeah, you can find partnership in all kinds of ways. And it doesn't have to just be based on, you know, sex at all."

Jess Romeo: Yeah. Well, I know we have to talk about religious trauma at some point. I I've been putting it off, but I know that it crafts so much of how you and I both got to do what we do, probably unconsciously for a while until it was more conscious. Tell us about religious trauma. What is it for people who don't know? And what's your relationship to it?

SC Nealy: Well, religious or spiritual trauma can - you know - it's going to look a little bit different to everybody, right? But the general principle is that it's like adverse experiences within religious or spiritual settings or with religious or spiritual people or leaders that lead to either struggles with mental health, identity, any other form of like things that impact trauma.

It is a century old concept, more than a century old concept. And yet the first time it was really referenced in mental health was like 2011 when like religious trauma syndrome was coined. But even that is still like - didn't get a ton - and still wasn't, you know, recognized in the DSM or anything like that.

And then I would say like 2019 is when things started to become a little bit mainstream and just utilizing the word religious trauma. The Religious Trauma Institute came about around then too, I think. So it's really only been like less than a decade, but also like five years that people have been talking about it, which is wild to me with something that has such a huge impact on people.

And when I started working with the queer population specifically, it wasn't really my intention to focus so much on religious trauma or to specialize in it. And then it just was like, every single client that is walking in the door has these similar experiences and also like shared experiences with myself as well. And certainly people outside of the queer population do too, but the statistics are incredibly high within the queer population. And so just the more I was seeing the impact of it, the more interested in it - got into really looking into it and helping people to work through it. And so that kind of is what led me to specifically focus on - I grew up in a very evangelical, pseudo cult situation down near the Blacksburg, Virginia area that was very rural, very isolated, all of the stereotypical narcissist leader and all of that, a lot of isolating you from the outside world, not allowed to have TV or radio or those kinds of things that would allow you to see or hear any ideas or opinions that are different than what they wanted you to believe, being in church all the time, being in youth group all the time, being indoctrinated at that early age.

And so that was just kind of the basis of like my entire childhood. And eventually that organization did dissolve as you most things with narcissistic leaders do when fighting happens and then people split. And then as I got more into the professional field and also have been doing my own therapy work as a client for - I don't know, 20 years at this point. I don't know if I'll ever be done with therapy.

Jess Romeo. Yeah, I'll - Yeah, I don't think I will either. I get that.

SC Nealy: So, yeah. So the more I just did that, I was experiencing it - the more, like, one, I found healing, you know, myself, and continuing to do that, and continuing to find that. And then two, I really found - I want to be able to help people in this specific - with this specific wound, how to work through it.

And so, you know, my very first nonfiction book comes out in like spring 2026 by Bloomsbury publishing and is on religious trauma and is more meant to be like a self-guided book on teaching people like what is religious trauma, how to identify it, how to forgive yourself for your own part in it, right?

Because the other aspect of religious trauma is that you also have participated in traumatizing other people. It's one of those few types of complex traumas that like - you - in order to get you to buy in, they had to make you complicit as well. And so in order to heal, you also have to like forgive yourself for what you've done to other people too. And that can be just - it just gets really complex.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. Yeah, and so many threads I want to pull on, but I think first, like, I think this happens less now, but as the term started to become a little bit more popularized, just like with any mental health term that's not yet in the DSM or maybe is not destined for the DSM at all because it doesn't belong there really, a lot of people I'd heard saying, "well, religious trauma - is that really even a thing? Like, are they just coming up with another term?" So like, what have you said? Because I'm sure you've had to say this to other people, for folks who have the response of, "is this really a thing or is it just life, part of human experience?"

SC Nealy: Well, trauma is part of human experience, yes. That's pretty hard to not have any. I mean, congrats to those who don't, but like, I have yet to run across one. But yeah, it took me three, maybe four years to get a publisher to pick up this book at all. And that was the feedback that I kept getting of like, "I don't think people really think this is a thing, or is this really a thing, or nobody is actually interested in this." Or people saying this would upset, like, religious people or this seems anti-religion, right? As if like calling out the areas that need to be improved on must mean you're anti-religion. So it took me -

Jess Romeo: That would be very on-brand though for how people have been against the discussion of things like critical race theory, queer folks in general. And like, if you are saying any part of this has wounds or has done something wrong, then you're saying all of it is bad. And that's not the case.

SC Nealy: Yeah. Yep. Ironically, and this is a controversial thing to even say, but I really think that Trump led to this book getting picked up. The more we have had division religiously and in the media, and the more people particularly in publishing and the arts and areas that are known to start revolutions are more seeking out books and guidance and content that pushes back on what's currently happening. So honestly, I think that that was a big lead into why it finally got picked up.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, no, I think that's probably true. And it's frustrating that something has to be seen - it's so reenacting of so many different traumas for a lot of people that something has to be seen at a manifest level across the nation for it to be seen as a need. You know, one thing I think about when it comes to religious trauma, because I do believe it exists, I know it does, I've experienced it too, is that not only when you've experienced it, has it been traumatic, right? The things themselves that happen, like telling you, "you as a person are wrong and you're going to be alone and you're going to hell because of who you are." Those things are damaging in themselves. But I think the really insidious thing about religious trauma is that the tools you've been given to cope with life's uncertainties and with challenges existed within the religion.

SC Nealy, LPC: Yeah, yeah. I think that's true with any sort of high control, high demand relationship. If you also think of it from a one-on-one relationship or a romantic relationship where somebody gets isolated from their friends or family and learns to have to depend on one person and then that one person ends up being abusive, yeah, it's the same thing. It's how you get people to stay. It's fear-based parenting. It's all of those things that are very effective in terms of obedience.

Yeah, that is one of the big parts of working with in religious trauma too is like before even delving into some of really hard stuff is helping people to build up the support systems and community that they have in other places as well as just the confidence in themselves to do so.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, because the healing has to exist within some form of community. And for so many people, that was the form of community. It's everything. Have you - in 2024, I started, you know, the way that I cope with a lot of things is I intellectualize first because that feels better than feeling. But I get there. But I read a lot about just about democracy in general to try and understand this whole authoritarianism thing. And what this moment meant in history, but also just about the trajectory of the Christian right in this country. Have you read Jesus and John Wayne by any chance?

SC Nealy: I haven't, no.

Jess Romeo: And this is not to throw more literature on you because for some people I want to respect that like not going there and not looking at it is just as fair as wanting to look at it. But I think it really hit home for me when I read that because the perspective is from someone who grew up in a Christian nationalist kind of setting, right? Grew up in a pretty fundamentalist place. And the compelling thing around it was about not only how they sort of co-opted Jesus as this very hyper-masculine figure and started using language that was way more revelations-based versus many other aspects of his person and personality, but the fact that Christianity doesn't just happen in church, that there is an entire media ecosystem. The TV that people are watching, the music that people are listening to. They've created entire ecosystems where you don't have to do anything outside the church. And in fact, you shouldn't.

SC Nealy: And a lot of times you don't even realize there are things outside of the church. There's like entire small towns that are all built around a church. Like that's the whole thing. Yeah. Yeah.

Jess Romeo: Mm-hmm. Yeah, that's the entire thing. Yeah. No, it's definitely wild. What are some of the things that you see? Because I always like the perspective of a therapist. I feel like we can help a lot of people feel less alone by sharing the fly on the wall kind of things that everybody's struggling with. What are the common things that people come in with or the themes that you see?

SC Nealy: Well, so the biggest one, obviously being a lifestyle of blame and shame, right? Like that someone needs to be blamed for everything and then you should feel shame for everything. The concept of like it being you are spiritually and morally superior for feeling shame, for feeling like, I'm not a good person, for feeling like, I'm always striving to be a better person, but I will always fall short, right? Like that's the Christian doctrine to believe you will always fall short.

Like that's a wild thing to tell people that no matter what they do in their entire life, they will always fall short. They will never be good enough. It's a wild thing to unpack that statement. And I don't believe that there would be any kind of loving god that would also then like tell their child, right? If that's what you want to go the father son route that would tell their child, yeah, honey, you're never going to be good enough for me. But I love you anyways. Like what?

Can you imagine, you have a six month old, can you imagine saying that to your kid? Can you imagine a world that would say that to our children? And that is the basic premise though, right? Of like - so much of different religions is you will never be enough, but if you love god and follow, you know, that's the best you can do. I just can't subscribe to anything that tells people that shame and feelings of inadequacy are the way to, I don't know, eternal life or whatever, right? That's the opposite of like love and self-compassion and all of these things that are also preached in the exact same book, right? So to me, that concept of like increasing somebody's self-esteem, self-compassion for themselves, how they see themselves as a human being and their worth, that's gonna be the biggest thing that comes in always first and foremost is gonna be that. That would be the most common.

I think the second most common after that is interpersonal relationship issues, generally from a disorganized attachment framework, right? Like a big thing in high demand, high control religions is the hierarchy of where you stand and where different relationships stand, right? So it's the rule of third, right? God, others, you, and you're always last. And so when you think about that from like an attachment theory lens and focus, that is very confusing and leads to lot of that like, you know, "I hate you, don't leave me, right?" Like, "I'll never be enough for you, but I am constantly clinging to you," right? It's the concept of avoidance and anxiety, avoidance and anxious attachment mixed up together, and just putting God or the church or leadership or whatever as that attachment anchor. So teaching people how to relate to other people in a different way through more secure attachment methods versus through that feeling of either anxiety or detachment or avoidance, that's probably the second most common thing.

Jess Romeo: Hmm. I don't think I'd ever put the put two and two together. I mean, thinking about - as an attachment figure, sure. But thinking about specifically disorganized attachment and maybe it could discriminate that a little bit from other attachment styles for listeners so that we - like how what's that link for you?

SC Nealy: Well, so there's four attachment styles, right? Secure being the one we all want and then the other three are insecure - and you've got anxious and you have avoidant and then disorganized is both of those together and so I have found more often than not that people with intense religious trauma fall more in the disorganized, right? Like some people always have a little more of one or versus the other but there is just that that disorganized piece of like I'm both wanting to run away from you and cling to you at the same time, right? And that is what is preached a lot. And it's very confusing.

And when you grow up in something that tells you like, you are worthy of love, but also you'll never be enough, like, of course you're gonna be disorganized. Like, the whole book is disorganized. Maybe that's just my opinion.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. Yeah, no, how could you not? I mean, it depends on that. It all completely depends on how it is, how you look at it too, because I remember my wife talks about she grew up in the South also and a bit of a different experience with religion than me, but pretty similar. Like we grew up in the same cultural time and religion. Taking a course about the history of the Bible was one of the most enlightening things for her. Like, "wait, this is a work of literature that we can examine it as a work of literature and think about what were the inputs, what were the times in which it was written" as opposed to "this is the literal word of God."

SC Nealy: Yeah, or even, yeah, as you're saying, like even looking back to like original - as original as we can get versions of the text versus like the versions that we have now, it's just like wildly different, even if you just look at different translations and things like that, it's so different.

I also think that there's a lot of healing that can come from looking at those original translations and seeing that maybe the purpose of the Bible and all of the different preachings in it was meant to be really good and helpful at some point. Like we've obviously - depending on what denomination you're in or any of those things, we've distorted it into so many different messages. But the concept overall of love and compassion and things like that, there's nothing wrong with that. That's fantastic. What happened? Where did we lose that?

Jess Romeo: Yeah, I - my read on it, at least right now, and would agree with a lot of people I've listened to about this, is just around people's attempts to grab power - that it gets completely bastardized by someone's attempts to grab power.

And that even, like, I remember talking about religion and gender diversity. One of the first references to cross-dressing that we see in the Bible is from Exodus. And it's described - we, you know, it's interpreted now as this is God saying that gender queer people and people who dress in different ways are wrong. You know, that it is a terrible thing. If you actually look at the context of the situation, it was about a pagan religious practice and it was about a leader who was trying to consolidate power by joining against the other, which was these pagans practicing their religion, which involves some cross-dressing. And it's just like, that is the common thread over and over again that I see is people trying to seek power over by dividing and conquer.

SC Nealy: Yeah. And that also is through how they translate it, right? The whole leviticus anti-homosexuality versus this "man shouldn't lay with boy". That's talking about pedophilia. They're fucking different. I don't know if I'm allowed to say that on the podcast.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. yeah, I swear a lot of fucks, yeah.

SC Nealy: It was very different. And there's so many trans people in the Bible. They just go by different names, or they're referred to in different ways, or they're called eunuch or they're talked about as they have some sort of like distortion physically, but we don't know if it was chosen or something happened. Like there's a lot of, there's a lot of trans people in the Bible, a ton. And some of them are in like high positions of like people look up to them or leadership or, you know, soldiers or things like that. Like they were respected in a lot of ways and depending on the passage on the story you read.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, there's a lot of queerness. I also watched a documentary called God and Country that's on Amazon Prime. There was a really helpful lead in to Jesus and John Wayne, but there was a pastor there who, you know, was a talking head multiple times throughout the documentary. And one of the most beautiful things that he said was about the religious right and how they say so much about what God said so little, and so little about what God said so much.

SC Nealy: Literally the best way to put that. Yeah.

Jess Romeo: Like no discussion about caring for the poor, caring for the homeless, caring for the downtrodden. Way too much discussion about trans people and queer people. And like, why? Just why?

SC Nealy: Yeah. Yeah.

Jess Romeo: Do people seek you out for religious trauma at this - at this point? Is that kind of the niche that you've specialized in?

SC Nealy: Yeah, they definitely do. That and I would say like mixed orientation relationships are probably like the biggest things I'm specifically sought out for. And when I say mixed orientation relationships, I'm referring to relationships where someone has transitioned genders or sexual orientations since they first met, which often means obviously was there at the start, but just now they're coming into that more.

Jess Romeo: Mm-hmm. Yeah. No, that's really great work.

Jess Romeo: And now for a quick word from our sponsors.

If you're a healthcare professional, you know that supporting trans and gender diverse patients isn't just about good intentions. It's about a lot more than that. And that's where my gender IQ comes in.

At my gender IQ, I offer a range of courses designed to help providers move beyond surface level inclusion and build true embodied trends affirming care within their practices. So whether you're an individual practitioner, a group practice, just starting out, are you ready to go all in, there's a program there for you. My flagship program, Transcend, is a mentorship experience for those ready to master trans-affirming care and pairs an unparalleled curriculum with weekly group consultation with yours truly. But if you need a foundation first, check out other courses that can help you build confidence step by step. Start by taking the Gender IQ Self-Assessment It'll show you exactly where to focus your learning. Because trans patients need you, and you're probably more ready than you think. So go to MyGenderIQ.com, take the and take it from there. That's MyGenderIQ.com where you can find the Gender IQ self-assessment and the right course for you. All right, back to the conversation.

Jess Romeo: What's sort of an ideal outcome for some of the folks who are seeking healing from religious trauma?

SC Nealy: Well, ideal outcome is that there isn't ever one outcome, that it's a continuous journey and exploration. But I think the things I look for most in my clients and also myself is comfort with asking more questions, comfort with not having answers, comfort with sitting in between, and allowing other people to do that too, not feeling the need to convince someone else, "no, what I believe is right and you have to believe it too." But allowing for your actions to speak first, you know, of compassion and love and care and all of that to show up first, I think tells me that somebody has done a lot of work in that area. I also think that healing from religious trauma involves a lot of starting your own identity search and work from the ground up, right? Like if your identity was really wrapped up in who your family was, who your church was, or any of those things, it takes a lot of time to then start fresh from the beginning, figure out who you are, and figure out and get comfortable with the fact that there's gonna be a lot of people who don't like who you are, and you have to be okay with that. And when you come from a religious background where you're supposed to be loved by everyone and taking care of everyone and all of those things, being unlikable is the worst thing in the world. But you have to be okay with that.

Jess Romeo: That had to be hard to come to. Because I'm imagining you had to go through that.

SC Nealy: Yeah, I was in a church setting for 15 years post leaving my family and they were a big source of support and family for me for a long time. And they were okay with me being queer as long as I wasn't publicly looking queer or acting queer. So if I was in a straight presenting relationship or marriage, they were okay with that because they loved everyone.

But when I left that and decided to pursue and be more honest with who I truly am, that was no longer acceptable. So that's also been something to work through. I thought that that was a safe and healing space to explore both myself authentically and my religious and or spiritual beliefs. And then I realized, no, it was only within the guidelines of who they wanted me to be. The moment I stepped outside of that, I was no longer welcome.

Jess Romeo: It sounds like - like for all of our journeys, knowing that full safety within a religious community is something that I don't know - I don't know if I'll ever be able to embrace it. I think I'll always have my hackles up a little bit. And like knowing which parts of like my survival response - I like to imagine just sort of a sentry. That's the language I use for a lot of people. Like my sentry will continue to be on guard, but when can my sentry take a break? that's just -

SC Nealy: I think that -that is like just, it's a learned response, right? At this point, to genuine experiences that you've had and you have to have that - like I was actually - was just - I had a meeting earlier today with someone who is a leading figure in like spiritual, integrated psychotherapy, which is wonderful. Like there's absolutely nothing wrong with that. That being said, anytime I meet with somebody who has a masters of divinity and practices that, and even if they are very progressive, immediately I feel- I feel anxiety. I feel like, "are you safe? Am I allowed to be queer around you? Am I allowed to say something negative about religion and you not kick me to the door?" And they were great and they were wonderful and very opening and asked me to come in and do it, explaining our religious trauma and all of that. So they were great.

But I even said that to them when I was talking to them. was like, I feel - just in your presence, I feel anxiety. Like, I feel anxiety of like, "are you going to hurt me?" And it's simply just because they're outwardly religious and that's it. But there are wonderful people out there who are religious. But yeah, I think that innate response of like, "gosh, I need to be careful" is always gonna be there for sure.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, and think having to respect that response, you know, because it is keeping - it keeps you safe. Like it helps keep you safe.

SC Nealy: Yeah. Yeah. But also being willing to be uncomfortable and put yourself in scenarios where you might get hurt if it might be worth it.

Jess Romeo: When you do trainings on religious trauma, like what have you not, I know - there's a lot we haven't talked about here that you would in trainings, but what else would you want to say about it? What's important to know?

SC Nealy: So I think it depends on the population of who I'm talking to. If I'm talking to therapists and doing trainings with therapists, one of the biggest things I'm talking to people about is their hesitancy and fear around even broaching the topic, right? So many therapists are afraid to even ask or - "I might say something that's offensive or culturally or religiously inappropriate" or like, "am I gonna be saying something that's more about my bias or not or how do I bring it up to begin with" or, know, 90 different things. And so really just like helping therapists become more comfortable talking about uncomfortable things. I think is something that you'd be surprised is so hard for therapists, but it's actually, I've seen a lot.

Jess Romeo: No, I've seen a lot of it too, in just teaching about trans affirming care. People are very afraid to make a mistake. And it comes from, again, it comes from a kind of a good place. You don't want to hurt people, but I do think that there's, there's this middle space of needing to be able to step into a little bit of discomfort and being able to have a presence that the person knows are going to be safe, telling you that you've made a mistake too.

SC Nealy: Yeah. Yeah.

Jess Romeo: Are there specific ways - since you specialize in it, it may not be as helpful for a generalist, but like somebody at community mental health, like, how - what are good ways to ask about it? How do you ask about things like this in your intake form? How do you open up conversations about religion and religious trauma?

SC Nealy: Well, I think most intake forms should have how do you identify from religious or spiritual belief, or you should be asking - the same as you're asking what medications do you take, you also want to ask what cultural background did you grow up in, and how does that show up in your life today? What religious background did you grow up in, and how did that show up in your life today? Those are just important historical questions in any sort of biopsychosocial that you're getting.

And when it comes to religion, it's specifically important to ask from the historical standpoint, because a lot of people will grow up in a religion and then leave. You know, we've seen this huge exodus from religion - however, after that exodus happened, so many people don't realize how impactful that first 18 years was. And so they don't naturally bring it up themselves in therapy very often. It's only if you ask and you're like, you know, how did this and this happen, right?

Or like - and you start to put the pieces together for someone that they'll start to be like, "yeah, maybe that did have an impact on me. Yeah, I did talk about that in youth group. Yeah, we did." And they start to put those pieces together. I have a client who was a former missionary kid and one of their parents died during childbirth overseas. Awful circumstances, hard time. The whole evangelical have as many kids as possible, just breed, knock them out.

And on the anniversary of her parents' death, they went and did a cold plunge in the, I don't know, Chesapeake Bay or something like that. And they were like, "it's just gonna make me feel really better." And I was like, "did you baptize yourself in grief? And the feeling of grief, did you feel like you had to go baptize yourself?" And they had never thought about it like that before.

And then we were able to pull it back that every time they were really struggling, they literally baptized themselves and they just didn't even know it. And so it's like things like that where you start to pull apart like, "why did you do that? Why was a cold plunge in the water so important to you in that moment?"

Jess Romeo: Wow. Mm-hmm. That we carry the mythology after all those years - we carry the ritual. Yeah.

SC Nealy: Yeah, it washed everything away. They felt better after - things were washed away. It's very interesting how everything kind of still ties and we don't even necessarily notice it.

Jess Romeo: And I mean, like, I'm assuming you're coming from a framework too of like, asking the question and not saying, well, that's fucked up. Like, why should that do - that shouldn't be there. Cause that's from this terrible, harmful religion. Just like, no, but that's maybe where it's from. How do we feel about that?

SC Nealy: Yeah, yeah, because for example, with the baptizing thing, like, okay, if something you felt like you could wash something away in a pretty harmless way, fantastic. But let's also identify where it came from and why you feel that way. But there's nothing wrong with a cold plunge and if that would feel better, fantastic.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. That is interesting. Yeah. Cold plunges and that craze of cold plunges. feel like our biohackers baptism a little bit. It's kind of become that way.

SC Nealy: Yeah, it's very interesting, for sure. It definitely comes up a lot, especially with the holidays just passing and all the different traditions that people pull around the holidays that they maybe have secularized, whatever you want to call it, since it's - it's very interesting.

Which, by the way, I can go on a whole rant about the word secular. There's a lot of therapists out there who want to work with religious trauma or advertise themselves as working with religious trauma, but they advertise themselves as secular therapists. And somebody with religious trauma is not going to feel safe with a secular therapist, right? Like, that isn't a good angle.

Jess Romeo: Huh. Yeah, say more about this, because I don't think I had a radar on it that much.

SC Nealy: Well, it kind of goes back to the black and white thinking, right? Of like, if you grew up in an evangelical setting and you heard nonstop, don't do secular things or listen to secular music or be around secular people, right? Like it's a negative thing. And so you're automatically going to feel like shame or excitement going to see a secular therapist. But what it does is, it already tells you in advance what the therapist believes and how you should also believe. And that to me is where it's problematic, right?

Like even if the therapist is secular, whatever you want to, whatever secular means to people these days is fine. But like, why does it, you know - it automatically tells you if you go to that therapist and you choose to stay in religion, is that therapist going to judge you? Is that therapist going to say you're doing the wrong thing?

Jess Romeo: Interesting. Yeah, I don't think I've seen people market themselves that much as secular or noticed it and how that's different from other identity terms. Yeah.

SC Nealy: Yeah, I use like more, like "non-faith based" will be kind of sometimes how I'll phrase it.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, and I think I know I've come across some, a lot of requests for specifically clinicians of a certain faith, you know, Christian counselors. And I always, I have the same, I think trauma response that you do around folks who have that at the forefront of identity as well. And I don't know how fair that is to some of those folks.

SC Nealy: Well, it's really hard because it's like both things are true. Like most people who reach out to you and I are probably also looking for queer identifying therapists and you, we want to build space for that and understand from a safety perspective and a lived experience perspective why they would do that. So the same comes true for those who are looking for, you know, Christian or certain belief or religious belief therapists. And I think that that's fine and that there's room for it.

I do think that though, there's also something to be said about the more - the more qualifiers you have for how your therapist identifies, the less likely you are ready to make any sort of actual change, right?

Jess Romeo: Ooh, I like that a lot. Say that again?

SC Nealy: If you want a therapist, well, the more qualifiers or identifiers you have for how your therapist is or who they are means you're less likely to change or want to change or be ready to change. You're probably still more pre-contemplative and putting in the work because you feel like you should versus you actually really want to.

Because if you think about it, like if you're like, well, I only want a female therapist who is Christian and also queer affirming and also this, you're not willing to actually be uncomfortable, right? You're finding someone who fits exactly what you're comfortable with and that's it. And so if you're not willing to be uncomfortable, you're probably not ready to actually make any change.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. Hmm. Like I know there would be people that would push back against that, but I also know there's truth to it. Like even if you do, that speaks to me to a person who needs to find some comfort in saying this somewhere that that's what they need before being able to take that next step at least.

SC Nealy: Which I think is fine with maybe one - figure out one identifier that's very important to you, right? But do you need all of the things the same? For example, I've often throughout my life seen female identifying or presenting therapists myself. However, the few times that I've seen male identifying therapists, I've been really, really challenged and it's been a lot of really hard work and I've grown so much because of that. That's just one example.

It's not to say that there's nothing wrong with being comfortable too. We all need comfort at times. And sometimes you're not in that window or readiness to like do hard work, but you just need comfort and support. And that's totally fine. But for those who really need change and help changing, it does help to have someone who can push that a little bit.

Jess Romeo: Yeah, I think the frame I'm thinking about was probably the same one you are about just the window of tolerance, right? Where someone is in their window at that moment, the difference being if the window for tolerance is really narrow that people can't at a nervous system level feel the difference between uncomfortable and unsafe. And that there has to be enough safety created to be able to widen the window and importantly distinguish between discomfort and lack of safety.

SC Nealy: Yeah, which is also why I think the last - the therapist is sticking to very, very specific identifiers of like, "this is me and there's no fluidity to that." The less that helps people without window of tolerance, right? Like I have clients who, they make a certain assumption about who I am in the first session and they hold that for a while. And then like six months in, I may say something or self disclose something that they're like, "whoa, whoa, whoa. I didn't - this isn't who I thought you were," right? And that actually will help us grow and then grow and stretch. Right. And move forward.

Jess Romeo: Well, we've talked about a lot of things. I want to know, What's something that's really exciting to you about your work in this moment in time?

SC Nealy: I'm really excited about, I think, that the more pushback happens on the queer population, the more we push back as well. And I think seeing the passion and excitement in people and just being in meetings lately with people who are providing to this population and reminding other people that we've been here before, that we've done this before, that really things have only been better for our population in the last like 10, 15 years, but like before that was terrible too. And so we survived it before and we can do it again. And I think just seeing that level of like resilience and hope still pouring through all the cracks feels really exciting to me.

Jess Romeo: Mm-hmm, yeah. Yeah, I would say I feel hopeful about that too and that I got to see probably about a hundred different queer people individually in the weeks after the election results. And there's something really humbling and satisfying to know that out of a hundred people, there were a hundred different responses. Like the queer community is not a monolith. We are not all reacting in the same way. And we're definitely not fucking all reacting as puddles in despair.

That is not the case. That's not the predominant thinking. A lot of people actually feel like their molecules are organized towards resilience and resistance in a way that they just hadn't.

SC Nealy: Which is also like a trauma response from childhoods like that, right? That when you're in the middle of crisis, that's when everything gets calm.

Jess Romeo: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Mm-hmm. It's so funny how that works and also being able to have the framework of like, "okay, yeah, it's a trauma response and it's probably the thing that's gonna help me get through." Like, we'll be able to do this in these next few years and I'll do the healing that I can.

SC Nealy: So funny how that works. It's useful. Yeah, it's useful. Yep. Yeah.

The big thing I've been pushing on my little soapbox is that I want therapists and mental health providers and providers in general to stop being queer affirming. I think that when I see that in people's profile, it pisses me off because I'm like, you don't see that about literally any other demographic. You're not like, we're not doing that with other demographics. Being affirming is like baseline. That's the standard. That's just saying I'm not hateful. Like, I want to see people saying I'm queer and trans celebratory. If I don't see that in your bio, I'm not referring to you.

Jess Romeo: Yeah. I know people are just trying to use the language that they know other people are using, so I give people grace for saying affirming, and I probably do too in my language, but yeah. Yeah. No, thanks for that prompt. I'll take a look at my website. Because it's definitely - I mean, I am a queer and trans person. I'm not here to just tolerate, right? That's not what I mean by queer and trans affirming,

SC Nealy: Yeah. Yeah. I think we need to shift away from that. Yeah.

Jess Romeo: Well, what do want other people to know about? What else would you like other people to know about or info about where we can find you in your practice?

SC Nealy: My practice is LGBT plus counseling collaborative in Arlington, Virginia. And you can find us at our website, lgbtcounselingdmv.com or just counselingdmv.com.

We are taking new clients and we're bringing on hopefully more therapists this year. We're expanding. So we're also looking for good matches for our team in that way. And then the book on religious trauma is called Healing Sacred Wounds and comes out in like February or March of 2026. And so people are welcome to subscribe on the website to the newsletter if they want to find out when it comes out.

Jess Romeo: And I always like to end on a joyful note. I ask people what queer joy means to them. Like, what's sort of a moment from your life that gives you queer joy? Or how are you defining that in your life right now?

SC Nealy: I think I find most queer joy in community when I'm with and around a lot of other queer folks. And I have specifically tailored my life that that is kind of my life almost all the time. Sometimes I forget that straight people exist. And so sometimes when I meet a straight person, I feel queer joy because I'm like, you're out here too. All right. Great.

Jess Romeo: Mm-hmm. Like, "good for you. Good For you kid."

SC Nealy: Yeah, feel joy in it for sure.

Jess Romeo: That's so good. Yeah, like a recentering of queerness.

There was a post I saw on, the other day that someone was like, hooray for boys with penises and girls with vaginas. And then below it, was like, I'm sorry, I totally forgot that cis people existed for a minute. I was really just celebrating surgery and gender affirming care. That's amazing. Yeah.

SC Nealy: I love that. That's amazing.

Jess Romeo: Good. Well, thanks so much for being here. Really appreciated the conversation and hope we'll connect again soon.

Jess Romeo: Thanks so much for listening to the Gender IQ podcast. Conversations like this one with SC remind me that healing is never linear and that queerness in all its forms is not something to be merely affirmed, but celebrated, explored and centered in the work that we do. If you connected with what SC shared, I highly recommend checking out their work at lgbtcounselingdmv.com. You can also follow on Instagram at lgbtcounselingdmv.

And as always, I'm so grateful you're here, listening, learning, unlearning, and showing up for these deeper conversations. If you enjoyed this episode, share it with someone who needs it, and leave a review to help us keep the conversation going. Until next time, take care of yourselves and each other. We'll see you here for Pride Month.

With thoughtful honesty and a deep commitment to liberation, SC Nealy invites us to reimagine spirituality as a site of healing rather than harm.

🎧 Listen now 🎧

About your host:

Jess Romeo is a Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner, clinical social worker, mentor, and educator with a passion for making gender-affirming care more accessible, inclusive, and informed.

With years of experience seeing patients, training healthcare providers, and being queer & trans, Jess brings a nuanced, compassionate, and engaging voice to conversations about gender identity and social justice.

Through this podcast, Jess cultivates a curious and brave space to explore the realities, challenges, and triumphs of our lives—helping providers, allies, and community members reflect, deepen their knowledge, and take meaningful action.

🎙️ Be the First to Hear + Earn CEs!